Solving the Principal/Agent Problem

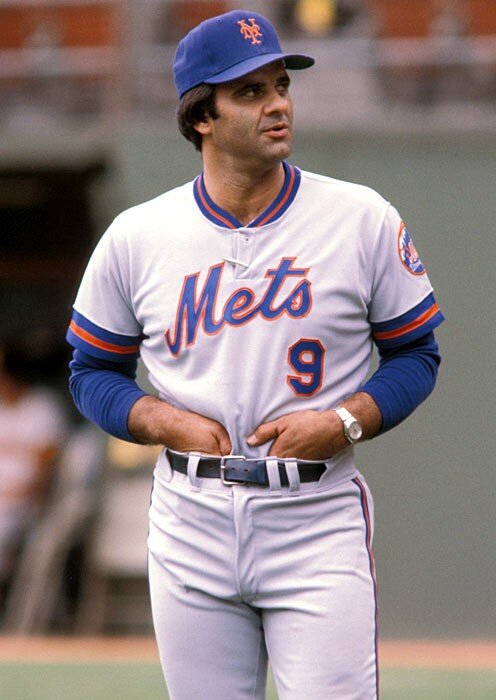

Joe Torre, 1977 (Player / Coach)

One can trace the roots of capitalism through family business. Since 718, the same family has operated the Hoshi Ryokan, a Japanese inn. The Antinori family produces wine in Tuscany, where they began laboring in 1385. In America, the Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Fords, Waltons, Lauders, Mellons, and others built great businesses across economic eras. Prior to the creation of business schools teaching management theory to aspiring professional managers, family businesses thrived because trust between family members was essential during this period while legal structures were weak, capital markets were nascent, and communications systems slow.

Given the development of legal systems, capital markets, and telecommunication networks, one could expect the power of family businesses to fade. Contrary to that hypothesis, family businesses comprise more than 90% of the world’s companies. BCG calculates that family companies represent 33% of American and 40% of French and German companies generating more than $1 billion of revenue annually. What explains the dominance of family companies then?

Agency Theory

According to the United Nations, “governance” means “the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented)”. Taken within the corporate context, corporate governance means making and implementing decisions that drive capital allocation, strategy, and operations. Prior to the era of professional managers, these decisions were taken by the leaders of family businesses largely responsible for specific regions. When the Rothschilds and Siemens expanded their businesses, they employed members of the family to manage the operations.

In 1881, Joseph Wharton established the world’s first business school at the University of Pennsylvania. Wharton believed the role of business was to advance society, creating new wealth and economic opportunities for all people. Thus, the world of professional management began, shifting the paradigm of corporate governance away from families and owners of businesses into that of agents.

Though not defined at the time, the development of professional management created Agency Theory, which defines the relationship between principals (shareholders of a company) and agents (professional managers of a company). According to the theory, principals of the company hire the agents to perform work. The principals delegate the work of running the business to the directors or managers who are agents of shareholders. The shareholders expect the agents to act and make decisions in the best interest of shareholders. Given agents are human, these managers may succumb to self-interest, short-termism, or opportunistic behavior that violates the interests of principals.

Milton Friedman wrote many influential pieces that helped create the Agency Theory. In a 1970 essay for The New York Times, Friedman wrote.

“In a free-enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires…the key point is that, in his capacity as a corporate executive, the manager is the agent of the individuals who own the corporation…and his primary responsibility is to them.”

Friedman established that managers work for shareholders. Friedman later also specified the responsibility of shareholders:

“to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

The modern era ushered in a new mass of professional managers, working as agents on behalf of principals. Friedman established that agents serve the needs of principals. Principals direct their businesses to increase profits. As a result, professional managers work to maximize profits for shareholders. Behold, the highly controversial adage: “maximizing shareholder value”.

Given that managers are rational economic actors, they occasionally make decisions contrary to the best interests of principals. The principal / agent dilemma defines the modern era of professional management. Family businesses avoid these agency issues because they own and operate their business.

The question, though, is whether eliminating the principal / agent conflict generates better returns.

What does the math say?

HHC ran a screen of public companies where CEOs owned >1% of shares outstanding (500 total companies) and compared it to the Russell 2000 index, excluding overlapping companies. Our >1% ownership index outperformed the Russell 2000 on three key metrics: 5-year historical revenue growth, returns on equity, and returns on assets. The average ownership of CEOs in the >1% index is 6.5% of the company, versus 0.3% of those in the Russell 2000 index (excluding the owner-operator cohort).

This data indicates that CEOs who own large portions of their business outperform professional managers in the public markets. Markets are short-term voting, long-term weighing machines. In these companies, management runs the business like they own it — because they do. Owner-operators generate the heaviest businesses over time by employing long-term thinking. We think this translates to all business builders — public and private. Owner-operators win and win big.

What can we learn from this?

The best way to navigate the principal / agent dilemma is to align yourself as an investor with an operator who owns significant amounts of their business. HHC invests in businesses where the management team owns significant portions of the business. We like owner-operators because they end up thinking quite like us. We feel strongly this aligns the interests of our capital, with that of the managers.

We feel the approach of aligning HHC’s capital with that of owner-operators represents something unique within the traditional private equity universe. Whereas traditional private equity firms seek to align the interests of their LPs and management teams exclusively through large option pools, we feel this creates issues of alignment despite the good intentions. In these scenarios, management teams pay no cash upfront for ownership stakes in companies they manage and receive a percentage of the value created — incentivizing risk taking. With no principal to protect, managers are misaligned from shareholders at the start. While we believe in sharing value created through option plans, we also want managers to risk their own wealth alongside ours from Day 1. We sleep well at night knowing our investments are aligned with that of the management teams operating the businesses every day.

—

Alexander Stacy

View the original article here.