How Interest Rates Impact M&A

Midjourney.

Over the last fifteen years, zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) altered capital markets by impacting discount rates, which created a competitive advantage for private equity firms relative to other buyers of assets. This competitive advantage derived from the fundamentals of asset pricing – discounted cash flows (DCF) – which discounts free cash flows by a weighted average cost of capital (discount rate). During ZIRP, private equity firms acquired assets at high prices driven by the following changes to their DCFs. First, private equity firms grew earnings through acquisition financed by private credit. Second, the weighted average cost of capital deployed by private equity firms declined due to the increase in debt as a percentage of total capital deployed. Lastly, private equity firms experienced fewer company failures due to the availability of capital. As a result, private equity crowded out other participants for business ownership – notably large strategic acquirers and the public markets. With the increase in interest rates, traditionally lower cost capital providers – public markets and large strategics – will likely regain market share within the capital markets as interest rates remain higher for longer. As business builders, Hudson Hill focuses on building great companies starting in the lower middle market that create value through organic growth and margin expansion by offering products and services that customers value. Ultimately, these changes in financial markets do not impact Hudson Hill’s core strategy, but rather the ideal monetization path for our business building efforts.

Discounted Cash Flows

The price of an asset is typically determined by the discounted value of its projected free cash flow. Discount rates are determined as a function of the total debt versus equity deployed in a company and the corresponding returns required by investors for each. Discount rates represent the returns investors target to compensate for receiving free cash flows at various points in the future. As you can see below, cost of capital declines as perceived failure risk declines. Investors pay more for the right to receive Apple’s future earnings than their local bakery. In the same way, private equity investments in small businesses must offer higher returns to investors than buying shares of Apple. The position in the capital structure – debt versus equity – also determines the size of this spread as you can see below, as the ultimate risk of capital impairment is lower the higher you invest in a capital structure. During ZIRP, private equity firms increased the percentage of debt to total capitalization, thereby reducing the weighted average cost of capital – or discount rate – of their portfolio companies.

Hudson Hill

Company failures compress the realized returns of assets from those expected when investors completed their initial investments through asset impairment. As you can see below, markets price a wide spectrum of expected returns based on company size and risk of failure, but over time the realized returns compress towards the long-run historical average return for asset classes (in the case of equities 8%-15% depending on company size). Investing in smaller companies offers the opportunity for higher returns, but the failure rate can overwhelm the potential return opportunity.

Hudson Hill

This dynamic, in part, describes the rise of the private equity industry. Private equity firms offer diversified portfolios to investors that more closely map towards the expected real returns of the asset class. As you can see below, failure rates for companies declined materially during ZIRP, causing the traditionally riskier asset class of private equity to deliver higher realized returns than their traditional risked adjusted return targets would indicate.

Source. Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (1985-2000: FFIEC 031 through 034; 2001-: FFIEC 031 & 041).

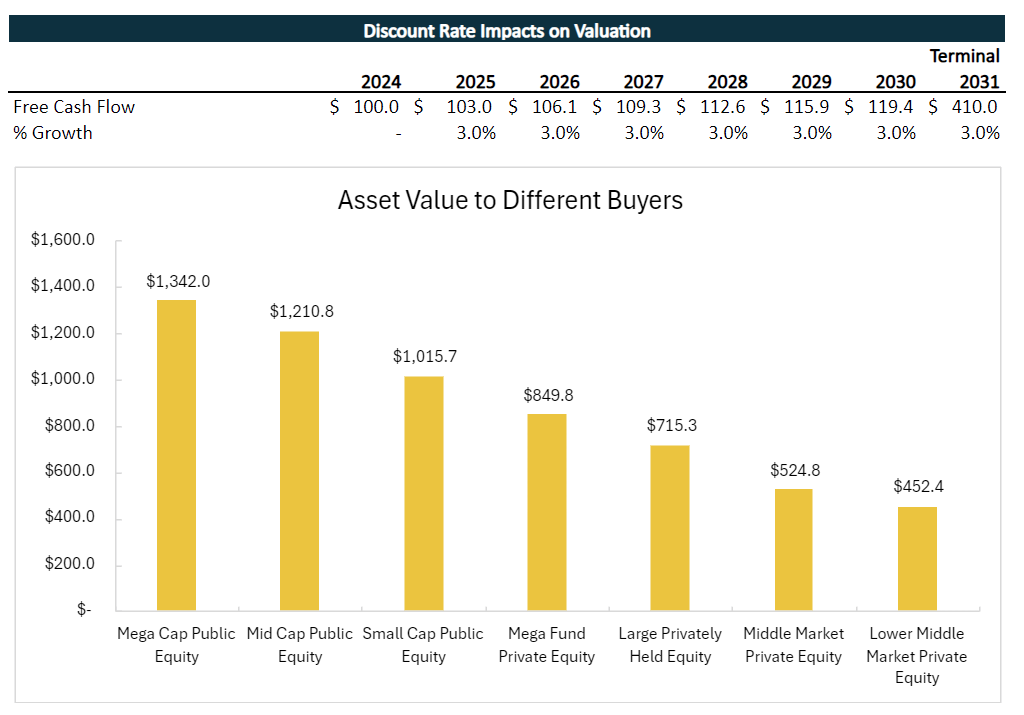

Within the M&A market, the discount rates of buyers determine the value of a stream of free cash flow. Large public companies target 8%-10% annual returns for shareholders, which means they can pay higher prices for companies. Private equity managers target 20%-35% annual returns, which traditionally disadvantages them when buying assets also targeted by large companies and public markets investors. In the example below, an asset generates $100 of free cash flow, growing 3% annually. As you can see, valuing the asset at the various discount rates of potential acquirers drives different values. For this reason, public equity investors traditionally paid the most for companies, with smaller investors like private equity firms paying the least.

Hudson Hill

Over the last fifteen years private equity emerged as the leading buyer of assets, outbidding public and private strategic buyers, while shrinking the universe of publicly traded securities. The number of public companies per capita in the US is down nearly 70% since 1996 (according to FRED), while the number of private equity owned companies is estimated to be nearly 11,500 in 2024 (according to IBISWorld), up from less than 1,000 in 1996 (according to World Bank).

Implications for Private Equity

Private equity firms benefited from ZIRP by acquiring companies that could execute a significant amount of M&A during their ownership. Private equity firms accessed credit markets that allowed them to leverage their portfolio companies up to 8x debt to EBITDA. Typically, public company investors prefer companies to operate with less than 2x debt to EBITDA. The low cost of interest also enabled private equity firms to increase the total amount of debt deployed as a multiple of EBITDA by ~75%. Private equity utilized this leverage capacity to pay high prices while continuing to deliver attractive returns to investors. As you can see below, ZIRP enabled private equity firms to generate their target equity returns through debt funded acquisitions – reducing the reliance on initial valuations and organic growth to create value. ZIRP inverted the normal functioning of public and private markets by introducing private equity as the structurally high bidder, outcompeting public equity, which traditionally offers the lowest cost of capital. While public company regulatory costs are certainly high, the cause of this secular decline of public companies is likely the low cost of debt versus regulatory arbitrage deployed by private investors.

As interest rates increase, the market forces that contributed to increased private equity market share in M&A will reverse. The ability to execute on acquisition heavy growth strategies after paying high purchase multiples will be difficult, reducing the free cash flow growth in private equity-backed company DCFs. The higher cost of debt will also increase private equity buyer discount rates causing their valuations to decline. Lastly, the failure rate of private equity companies will increase, thereby increasing the cost of equity deployed, further reducing valuations. As a result, private equity investors will need to develop different strategies to address the new conditions within financial markets. At the same time, large private strategics and public equity investors – both through IPOs and through publicly traded companies – will likely regain M&A market share, as they will resume the lowest cost of capital position within the capital markets.

Conclusion

ZIRP impacted the normal functioning of the capital markets through the emergence of private equity and credit, which created the highest bidder for companies in the capital markets. With the end of ZIRP, capital markets will find a new equilibrium more consistent with pre-2008 financial markets, creating opportunities and challenges for incumbents and emergent competitors for financial assets. For private equity, the successful strategies deployed during ZIRP may struggle to retain their competitive edge, forcing financial sponsors to adopt new ways of creating value for investors prospectively. Owners of financial assets – regardless of funding source – will need to generate differentiated value to help companies grow in a capital efficient manner.

At Hudson Hill, we believe the firm is well positioned to capitalize on this opportunity through its differentiated, value-added approach to investing that focuses on building companies with defensible value propositions, operating in large markets, that can grow market share organically over long periods of time. Hudson Hill makes investments in companies with less than $250 million of enterprise value, a space less impacted in recent years by the impacts of ZIRP as these companies belong in the private markets outside of the portfolios of larger strategics. When thinking about exiting companies, business owners should once again focus on public markets or large strategic acquirers, as these options will present the highest valuations. The private equity buyer will likely return to its position as the highest cost of capital in M&A markets. The market forces impacting the M&A markets that created winners and losers over the last fifteen years will reverse, presenting an exciting new environment to challenge incumbents across industries. As we enter this new phase within capital markets, it will be important to challenge all closely held assumptions based on what worked over the prior fifteen years. Hudson Hill expects its approach to partnering with founder owned companies with substantial organic growth potential to lead in the new environment.

—

Alexander Stacy

View the original article here.